How Textiles Have Changed with Technological Innovation

SDTB / C. Kirchner

In the 18th century spinning and weaving mills were at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution. In 1728 Jean-Baptiste Falcon developed an improved control mechanism for semi-automated looms, using interchangeable punch cards. Each punch card was literally a unit of “working memory,” as it contained commands for the next step in the work process. In 1805 Joseph-Marie Jacquard also used punch cards for the first fully automated loom. Thus the binary principle of digital technology was established in the realm of weaving more than 200 years ago: if the governing needle hit a hole, the warp thread was raised; if there was no hole, the thread remained in place. The Jacquard mechanism is the key element in the mechanical loom displayed in the foyer of the Deutsches Technikmuseum.

The Versatility of Textiles Enables New Applications

SDTB / N. Michalke

The exhibition highlights the great versatility of textiles. They don’t have to be soft and beautiful. Indeed, some are firm and extremely robust. Do we need a cuddly wool sweater, or a lifesaving safety belt? The nature of a textile depends on the material used, the way it is processed, and the textile structure. Thus a wool sweater is just as much a textile as a polyester safety belt. Visitors to the exhibition will learn what makes the difference. Knitting, weaving, felting, and braiding are the traditional techniques for giving fabric an interlooped (knitted) or an interlaced (woven) structure. For a safety belt one meter long, 30,000 meters of synthetic thread must be woven together. All kinds of material can be used. Cotton, silk, precious metals, and high-tech materials can all be made into textiles.

What We Wear Influences Globalization – And Vice Versa

SDTB / C. Kirchner

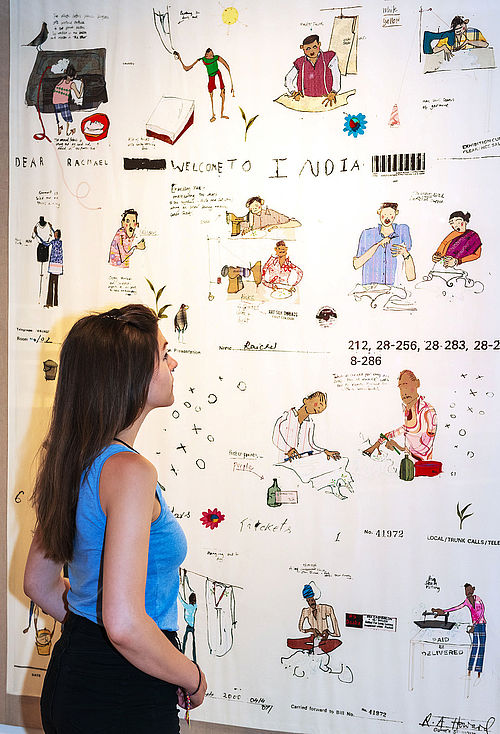

The textile industry was not only the birthplace of industrialization. It has also played a leading role in globalization. Using the example of India, the exhibition explains how globalized production began and how it has developed – technological innovation in the north, labor-intensive production in the south. Clothing is one of the most important examples of the fact that manufacturing is no longer linked to need. This is only in part due to globalization. Indeed, much more important are patterns of consumption. A sustainable form of recycling used to be the norm. Clothing was handed down and worn until it was worn out. It was darned or patched when necessary. Today we get rid of clothes that have barely been worn once, simply because they have gone out of fashion. We recycle them by sending them by the ton back to the countries they came from. Or worse – we just throw them away. Both issues are central to sustainability. The exhibition features a pair of underwear from the 1920s that has been darned in several places. It symbolizes how our relationship to clothing has changed.

Highlights

Jacquard loom

This mechanical loom with two Jacquard mechanisms could make up to 18 different kinds of trimmings, i.e. patterned ornamental bands. It was used especially to make trimmings for traditional costumes. It was in industrial use in Roth near Nuremberg until 1990. Now its operation is regularly demonstrated in the foyer of the Deutsches Technikmuseum.

1920, gift of Karl Grimm GmbH

Boots

Waltraud Janzen crocheted these unusual boots out of thin brass wire, using a thick hook. The stitches are dense, including single and double crochet stitches. For other articles of clothing made the same way, Janzen was awarded the “Golden Bobbin” at the Ninth International Lace Biennial in Brussels in 2000.

Waltraud Janzen, 1998

Steel-wool knitting machine

This circular knitting machine for making steel wool functioned just like a sock knitting machine. The latch needles are successively pushed up by triangular heads to form the stitches. The needle opens, the steel thread is inserted, and the needle closes and is pulled down through the preceding stitch.

ca. 1920, on loan from the Fabrikmuseum Roth

Folding spinning wheel from India

With this small, hand-operated spinning wheel, called a charkha, cotton yarn was spun for household use. This particular spinning wheel’s dimensions are 30 x 20 x 10 cm – making it a “boo charkha.” In 1920 Mahatma Gandhi, a leader in India’s fight for independence, called on the people of India to revive this traditional spinning technique and use it to make their own clothing, as a way of taking a stand against the industrially produced clothing of their British colonial overlords.

ca. 1940