Sugar: A Substance of (Nearly) Limitless Possibilities

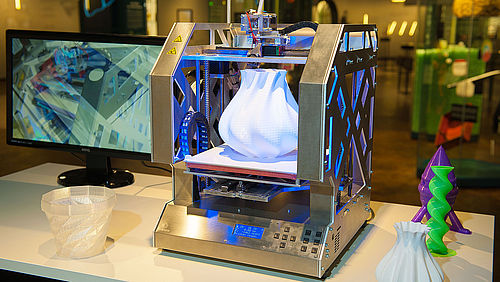

The exhibition “Sugars and Beyond!” is the new home of the Sugar Museum, which was opened in 1904 in the Institut für Zuckerindustrie (Sugar Industry Institute) in Berlin’s Wedding district. The exhibition showcases the fascinating spectrum of sugar’s applications and the social changes it has set in motion. The “queen of crops,” the sugar beet, stands for the agro-industrial revolution of the past. The future is symbolized by new technologies that use sugar molecules for energy storage, as bioreactors, and as a raw material for 3D printing.

SDTB / H. Hattendorf

We Are What We Eat – We Are Sugar

When we refer to sugar in everyday life, we usually mean sucrose, also called table sugar or granulated sugar. This sweet, white substance, which makes so many foods so irresistible, was a luxury good in Europe 500 years ago, a treat for kings and queens. Between 1690 and 1790, however, 12 million metric tons of raw sugar were imported to Europe. Today Europeans consume this amount of sugar in less than one year.

Initially sugar came from sugar cane that grew in overseas colonies. Growing and harvesting sugar was thus closely connected to the exploitation and enslavement of mostly African people. Later, however, the sugar beet became a source of domestic production. The scientific foundation for cultivating sugar beets was laid in the mid-18th century by two chemists in Berlin, Andreas Sigismund Marggraf and Franz Carl Achard.

SDTB / C. Kirchner

“Sugars and Beyond!” explains how this innovation led to an economic revolution in agriculture. By the late 19th century, beet sugar had become the German Reich’s chief export good. The exhibition also features the machinery that made this possible, from the beet topping plow to the furrow opener to the modern harvester in Ferrari red.

But it’s not only table sugar that ends up in our bellies. In fact, there are any number of sugar molecules that can be joined together into complex chains. Cellulose and chitin are omnipresent in nature. Even in our own bodies, all manner of sugar compounds make up vital structures, including DNA. We eat sugar. And we are what we eat.

SDTB / H. Hattendorf

Sugar: Raw Material, Source of Energy, and Medical Applications

SDTB / C. Kirchner

The polysaccharide cellulose is a structural material in plants. It has been used by human beings for thousands of years, for example in the form of wood as a building material and fuel. It was also the base material in early synthetics like celluloid, which was long used for motion picture film stock. And the future is degradable synthetics, whose raw materials are also usually sugar molecules.

Sugar is created in photosynthesis and thus can be thought of as containing stored solar energy. This energy can be exploited. All forms of bioenergy ultimately go back to sugar. The most common is the fermentation of ethanol, which we know from gas stations as a ten-percent additive in gasoline (E10). But as the exhibition shows, sugar also plays a part in other sources of bioenergy such as biogas and biodiesel. The numerous sugar molecules in the cells and proteins in the human body also have applications in medicine.

In bioreactors, certain bacteria can produce sugar by means of photosynthesis.

SDTB / C. Kirchner

A view of the Silver Cabinet, where numerous historical sugar bowls are displayed.

gewerkdesign, Berlin

Sugars can be used to produce modern synthetic materials that are biodegradable.

SDTB / C. Kirchner

Highlights

Preserved exoskeleton of a Japanese spider crab

The shell of this Japanese spider crab (Macrocheira kaempferi) is made of the polysaccharide chitin. It is the largest species of crab in the world. These animals live in the Pacific Ocean around Japan at a depth of 300 to 400 meters. Chitin is an essential component of the exoskeleton. This is the case for all arthropods, which include not only crabs but also spiders and insects.

undated

Sickle for topping beets, 1926

A master smith gave this sickle to a young women as a wedding gift in 1926. After beets were dug up, harvesters used sickles to scrape clumps of dirt off them and then remove the tops and leaves. This particular sickle was used for at least 26 years. Nevertheless, the curved, tapering blade never needed to be sharpened. Constant use kept the edge fine.

1926, gift of Wilhelm Barte

Oligosaccharide synthesizer, 2006

Professor Peter Seeberger developed a device at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that synthesizes sugar chains from individual molecules: an oligosaccharide synthesizer. Physicians can use these sugar chains to fight diseases. The prototype of this device, which has since been exported all over the world, is on display at the “Sugar and Beyond!” exhibition at the Deutsches Technikmuseum.

2006, on loan from the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft

Painting, "Friedrich Wilhelm III Receives Achard"

An historic moment: Franz Carl Achard, chemist at the Berlin Academy of Sciences, presents the first beet sugar to Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III. But the meeting, depicted in this painting by Clara E. Fischer, never happened. Instead, in 1798 someone else gave the king a sugar sample that had been refined for Achard in the Zuckersiederey Compagnie (Sugar Boiling Company) in Berlin. As a result, the king financed the building of the first beet sugar factory, in Cunern (now Konary, Poland) in what was then Silesia.

Clara E. Fischer, 1903